Yates Account

Join now

Create a Yates account today!

Sign up to join the Yates Garden Club for monthly e-mails packed with seasonal inspiration, tips for success & exclusive promotions.

Plus if you’re a Garden Club member you can take part in the Yates Growing Community - a blog to share successes, get advice & win prizes in fun challenges along the way!

Forgot password

Enter the email address associated with your account, and we'll email you a new password.

We live in interesting times!

Global economic disruption and food price rises continue to bite in NZ.

We’ve been talking with a lot of gardeners who are feeling financially stretched, so they’re turning to vegie gardening to take control of their living costs.

We saw this happening during the ‘GFC’ in 2008 and it’s even more prevalent right now – when the going gets tough, the tough get gardening!

This spectacular growth of interest in vegie gardening inspired us to have a look through our archives, to see how our great-grandparents (and their parents) coped with the big historical disruptions they lived through. What we found is fascinating – it seems getting into the garden and growing food is a time-honoured tactic to get through tough times.

The Spanish Influenza epidemic at the end of 1918 struck suddenly but subsided quickly. While it was a devastating pandemic here in NZ, it didn’t leave obvious traces in Yates gardening catalogues from the time. The same goes for World War 1, the ‘Great War’. Our theory is that for NZ gardeners the war still felt pretty remote and didn’t affect them day-to-day.

The Great Depression of the 1930s was a different story – rampant global inflation led to Yates encouraging customers to place early indent orders with locked-in prices, to provide certainty amid soaring costs. The Depression had a dramatic effect on NZ – export prices crashed, causing mass unemployment and slashed wages. It became very common to have a carefully planned backyard garden, to produce food year-round, supported by extensive bottling and preserving. Social Welfare had yet to be introduced; the ‘work camp’ alternatives to self-sufficiency were pretty grim, so home gardens became very important in people’s daily lives. Yates seed catalogues from this time were packed with options to suit self-sufficient gardeners. If you’re interested in how a Depression-era vegie garden worked, with tips on how to start up your own, have a look here.

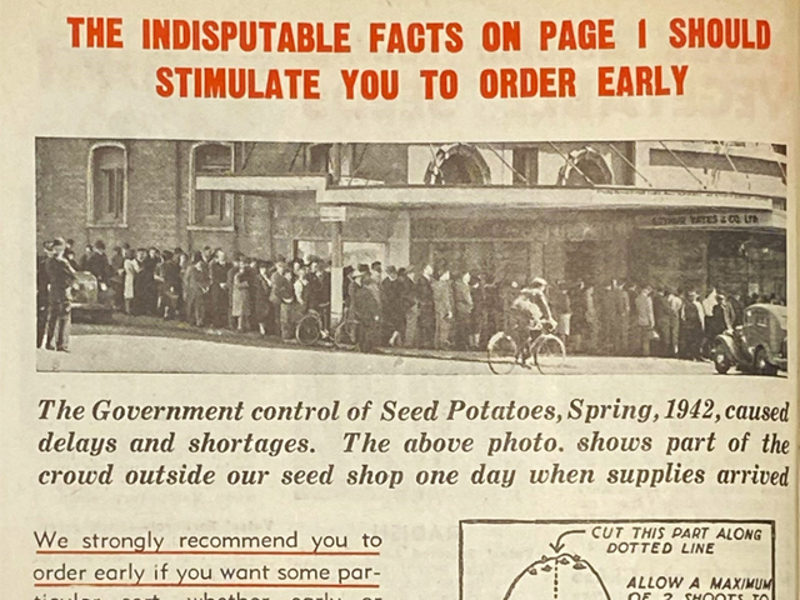

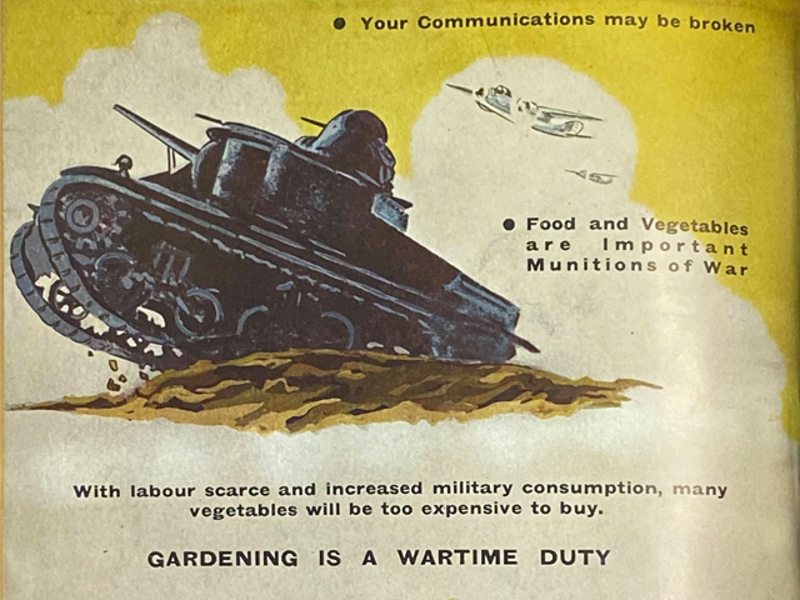

World War II put the brakes on the economy again – globally, entire populations were mobilised and put on a war footing; this was reflected here in Yates catalogues. NZ was contributing a lot of primary produce to Great Britain to aid the war effort, which resulted in local food rationing. New Zealanders were strongly encouraged by the government to grow their own vegetables for home consumption, with gardening portrayed as a ‘patriotic duty”.

With soldiers returning, by the end of the war there were 30,000 people on the waiting list for a State House, which resulted in a 1950s building boom of new houses on quarter acre sections - a deliberate strategy to create space for family gardens. Home vegie gardens continued to be popular throughout the 1960s, until increased car ownership allowed supermarkets to become the dominant, convenient food shopping destination.

After about 20 years of prosperity, during the 1970s the vicious cycle repeated itself, with global oil shocks and Britain joining the EEC. It was no accident that this coincided with the ‘Hippie generation’ desire to be self-sufficient and grow their own food.

Yates has been in business for nearly 140 years; over that time we’ve learned that home gardening to put food on the table won’t ever go away – it waxes and wanes in line with the economy, but it will always be the classic method to help get through challenging times. Whenever the going gets tough, the next generation of Kiwis hit their gardens!

Starting a 1930’s Vegie Garden

Classic tips from Great-Great-Grandma!

During the 1930s, having a home vegie garden to help take control of food costs was really important. The methods used back then are still excellent for a 21st century garden, so if you’d like to grow vegies to put food on the table, read on!

To make a classic tough-times garden work for you, planning is key. Work out what you want to grow, sort your list by seasons and plan out how long it takes to harvest. Get it down on paper, then get the seeds and materials together so you’re ready to go at the right time.

Also read up on the different methods of preserving and gather the equipment you’ll need for bottling, pickles, fermenting and drying. This allows you to extend the savings on your food budget all year-round.

Roll with The Seasons

The best mindset for a 1930’s Garden is to make the most of whatever is in season. Plan your meals around what the garden is providing – this means you’ll be enjoying generous lashings of fresh tomatoes and beans through summer, but next to none during winter. Great-Great-Grandma’s method to deal with this was to make hearty sauce out of all the excess tomatoes and store jars for winter. These days we have the luxury of freezing as well, so you can spread the seasons out a bit wider.

Making home-made sauces, jams and pickles was really important to help stretch things all year-round. The principle still works, even if you buy fruit in bulk when prices are lowest – you can spend a day making jam and set yourself up for the rest of the year.

Prioritise the really productive, bulky vegies that will deliver you substantial amounts for eating. For example, a half cabbage can be the backbone of a truly great meal. The other half could make extravagantly tasty kimchi, to save for a rainy day. Broccoli, cauliflower, beans, carrots, beetroot, tomatoes, zucchini, spinach, pumpkins and potatoes are excellent candidates and are all easy to grow.

There aren’t many rules, but this is one: only grow vegies you like – there’s no use growing things that you or the family won’t eat, if space is at a premium. Focus on the vegies you eat most often and are in your cooking repertoire. It doesn’t need to be all boring basics either; it’s a great idea to sow the vegies that are consistently expensive in supermarkets – capsicums, tomatoes and chillies are good examples. You don’t need to miss out on the tasty, interesting treats! If you end up with too much, you can pickle or freeze them, barter with gardening friends, or just give them away and brighten up someone else’s meals.

Speaking of brightening up a meal: plant plenty of herbs – even on a simple vegetable dish, they’re a sprinkle of tasty magic.

Sow Slow and Steady

Spread out your seed sowing week-by-week, so everything isn’t ready at the same time. Ideally you can harvest in the early season, mid-season and still get late-season produce.

If you sow both ‘early’ and ‘late’ varieties at the start of the season, you can extend your harvest period, because early varieties take less time to mature, compared with late varieties which take a bit longer.

Sowing 'little and often' maximises freshness and reduces the time pressure to use up vegies sitting in the fridge.

Use Every Bit of Space.

Have a critical look around your garden area to max out your planting space. It’s often the case that the sunniest spots are on paths or paving – these spots are ideal to place temporary polybags to grow spring and summer crops. When the season ends you can remove them without leaving a trace. Generous PB25 polybags (15L volume) or PB40 polybags (25L) are an ideal choice, as smaller bags dry out faster in hot weather.

Take advantage of sunny house or garage walls to grow tall tomatoes; if you hang stretchy cotton plant tie from cup hooks under the eaves, you can spiral wrap it around the vines and gradually train them to full height.

In a small garden you’ll benefit from crop rotation to keep everything healthy – move vegies to a new spot every year (especially brassicas). Switch something else into the vacant spot - the old-school rule of thumb is to ‘rest’ the planting spot for 2 seasons, after that you can plant the original vegie back in that spot.

Let in the Sun

Classic 1930’s Garden layouts didn’t have high fences or border planting, to maximise sunlight hours to the vegie garden. To this day, very original State Houses have minimal, open borders. It’s why low chain link fences are so common on older sections – they let light through and they make a marvellous trellis. If you aren’t renting and have the opportunity to be ruthless, clear the decks to let as much sun onto your vegies as you can.

Re-use, Repurpose, Recycle.

Gardening doesn’t need to be expensive. We often joke that it would work out cheaper to just buy the vegies after paying for gardening equipment and supplies, but the mindset that works with a 1930’s Garden is to only pay for things that make a noticeable difference in your vegie output, like quality slow-release fertilisers or sparingly applied insecticides. For example, there’s an upfront cost with a pump sprayer but it pays for itself in the long run by allowing you to choose ‘mix it yourself’ concentrates instead of convenience ‘ready to use’ products. If you can get something for free, go for it. You can use old windows to make cold frames, scrap timber to build compost bins, or salvage sheets of glass to cover your seed trays. Never throw out a plastic pot, punnet or yoghurt container; after a wash they are ready for another round. Old polybags can be reused for several seasons, along with last year’s potting mix that you just tipped out of them. Put it in a pile, cover it and reuse it next year.

Go For Cost-effective Seed, But Don’t Ignore Hybrids.

It goes without saying that buying seed works out much cheaper than buying seedlings in punnets. Traditionally gardeners have prioritised open-pollinate ‘old favourite’ varieties, because there are more seeds in the packet and they can save seed successfully. Hybrid seed is generally pricier, due to the increased cost of production. Counter-intuitively, hybrid seed can be a superior choice for the home vegie gardener! In return for the higher price, hybrids have been purpose-bred to deliver more reliable and consistent germination, bigger, faster-growing and tastier plants, higher yields and better stress and disease resistance. If you’re relying on the outcome, hybrids give you more surety and confidence; it's why commercial growers insist on F1 hybrids.

Share

Share this article on social media